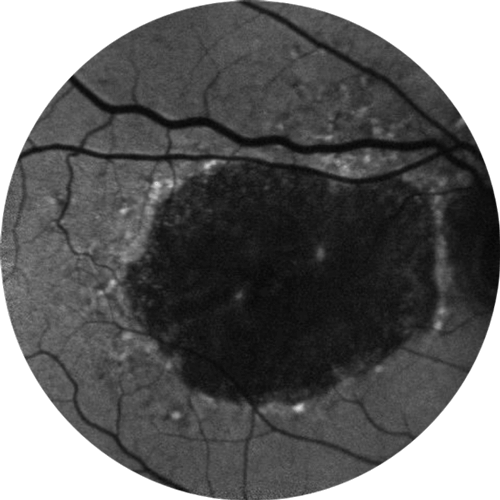

Geographic Atrophy progression is relentless and irreversible1-4

Geographic Atrophy (GA) is characterized by progressive loss of the photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and underlying choriocapillaris.1,5

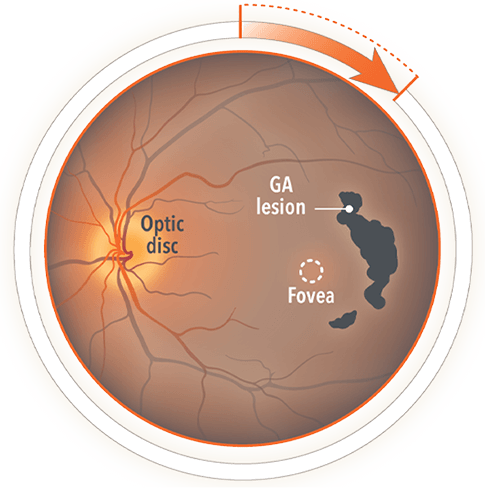

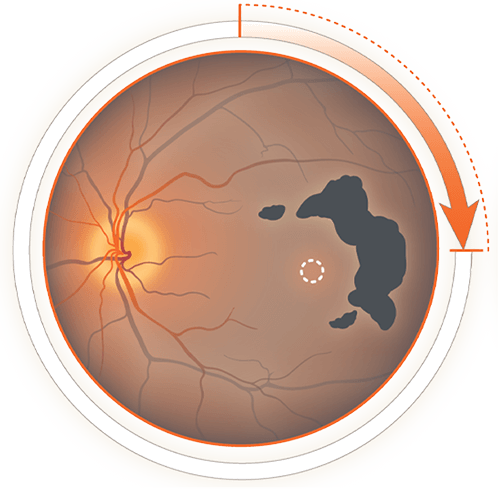

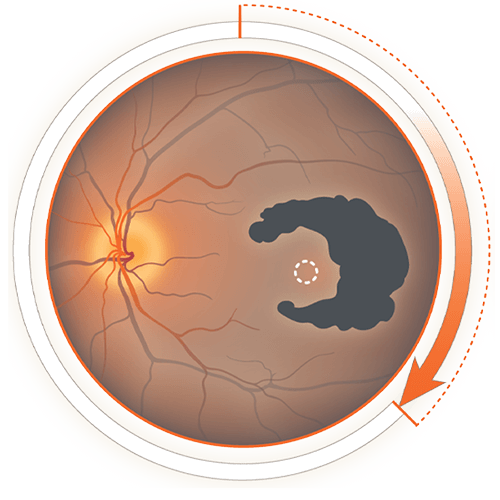

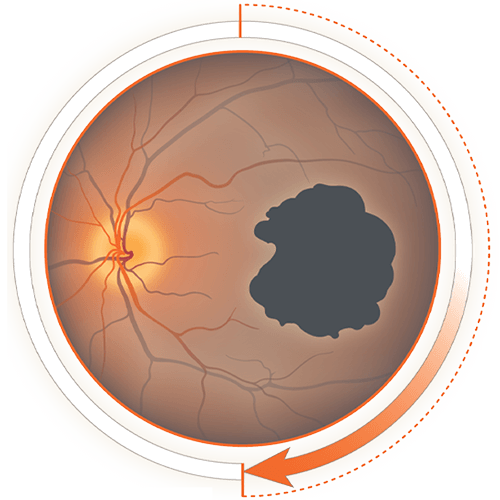

Regions of atrophy typically start outside the fovea and expand to involve the fovea, which – over time – leads to permanent loss of vision.5

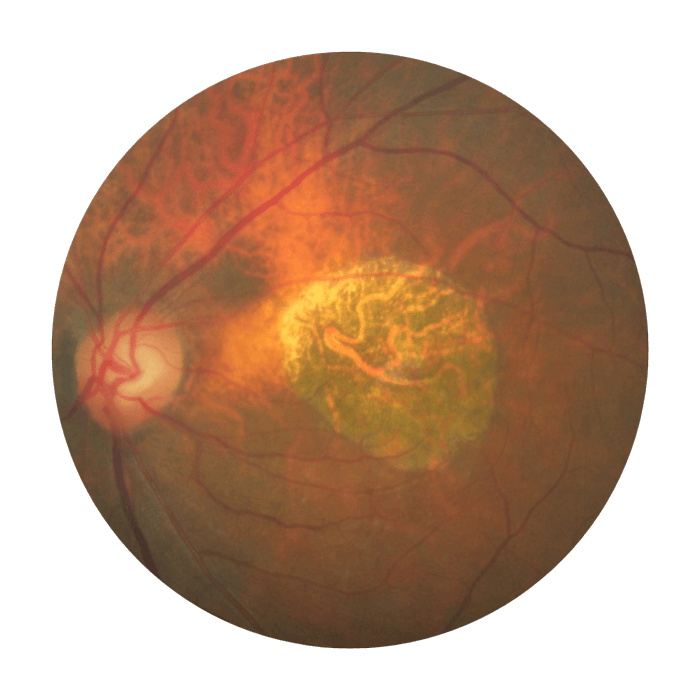

Colour fundus photograph of an eye with GA

Lesion growth may lead to

functional vision decline1,12,13

Visual acuity (VA) is poorly correlated with GA lesion size, and change in VA may not fully reflect disease progression.1,14 Even when VA remains relatively unchanged, functional vision declines as lesions grow.1,4,7-9

BCVA=best-corrected visual acuity.

Images courtesy of David Eichenbaum, MD, Retina Vitreous Associates of Florida.

Living with GA

“There’s going to be a day where I’m not going to be able to drive.”

Hear from Santi, an actual patient living with GA.

Santi was compensated for her participation in this video.

The following video was developed by Apellis Pharmaceuticals, and the patient was compensated by Apellis to share her story. It contains the views, opinions, and experience of Santi, a person living with Geographic Atrophy (GA). The video does not include individual treatment or medical advice. You should consult your doctor for medical advice or about any questions and concerns you have about living with GA.

Geographic Atrophy (GA) is an advanced form of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). GA is a leading cause of blindness that affects 5 million people worldwide.

VO: For me, even as a little girl, I was so visual – and I would just thank God just for everything I could see. I’m so amazed at things that are beautiful, and did I know that somewhere down the road I was going to get this diagnosis? I don’t know.

I have Geographic Atrophy in both eyes. Getting this diagnosis terrified me. I was afraid to go to sleep. I didn’t want to wake up and have lost the world. And I think we all get challenges in life, this was mine.

And when the Geographic Atrophy hit, it went down fast. And then things started to disappear, like a phone pole would be crooked and there’d be parts of that pole that I wouldn’t see. And then I was legally blind. I’ve always been very independent and very visual. To think of missing that bird that’s at the feeder or the bunny that crosses the street. If I couldn’t walk my dog.

Going down stairs is very scary because of the depth perception. I fell down my stairs here very badly. I immediately tried to minimize it, but I couldn’t get up. I was really hurting. I thought, “there’s going to be a day when I’m not going to be able to drive.” I sold my house. I moved where I could walk everywhere. You know, all these things to try to troubleshoot, but the hard part was the emotional part.

I have to feel useful. I started to go to this orphanage and just working with the kids, talking to them, I started to feel such a sense of peace. I was always the helper. I was always the one taking care of people. I have to find that middle road of being able to ask for help with grace and appreciation.

I hope that it doesn’t come to the point where I don’t see it. You know, I don’t want to miss one sunrise. In every challenge I’ve ever had, there’s always been a gift that hasn’t been apparent right away. But if there always has been, I’m assuming there always will be.

Want to stay connected?

Sign up for updates and information from Apellis.

References:

- Boyer DS, Schmidt-Erfurth U, van Lookeren Campagne M, et al. The pathophysiology of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration and the complement pathway as a therapeutic target. Retina. 2017;37(5):819-835. doi:10.1097/iae.0000000000001392.

- Lindblad AS, Lloyd PC, Clemons TE, et al. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Change in area of geographic atrophy in the age-related eye disease study: AREDS report number 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1168-1174. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.198.

- Holz FG, Strauss EC, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, van Lookeren Campagne M. Geographic atrophy: clinical features and potential therapeutic approaches. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1079-1091. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.023.

- Sunness JS, Margalit E, Srikumaran D, et al. The long-term natural history of geographic atrophy from age-related macular degeneration: enlargement of atrophy and implications for interventional clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.016.

- Fleckenstein M, Mitchell P, Freund B, et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369-390. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.08.038.

- Rahimy E. Evaluating geographic atrophy in real-world clinical practice: new findings from the IRIS registry. Presented at: American Academy of Ophthalmology Meeting; November 14, 2020; virtual meeting.

- Sunness JS, Rubin GS, Applegate CA, et al. Visual function abnormalities and prognosis in eyes with age-related geographic atrophy of the macula and good visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(10):1677-1691.

- Sunness JS, Applegate CA, Haselwood D, Rubin GS. Fixation patterns and reading rates in eyes with central scotomas from advanced atrophic age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt disease. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(9):1458-1466.

- Sunness JS, Applegate CA. Long-term follow-up of fixation patterns in eyes with central scotomas from geographic atrophy that is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1085-1093.

- Sivaprasad S, Tschosik EA, Guymer RH, et al. Living with geographic atrophy: an ethnographic study. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8:115-124.

- Singh RP, Patel SS, Nielsen JS, et al. Patient-, caregiver-, and eye care professional-reported burden of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmic Clin Trials. 2019;2(1):1-6.

- Kimel M, Leidy NK, Tschosik E, et al. Functional reading independence (FRI) index: A new patient-reported outcome measure for patients with geographic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):6298-6304. doi:10.1167/iovs.16-20361.

- Sadda SR, Chakravarthy U, Birch DG, Staurenghi G, Henry EC, Brittain C. Clinical endpoints for the study of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2016;36(10):1806-1822. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001283.

- Heier JS, Pieramici D, Chakravarthy U, et al. Visual function decline resulting from geographic atrophy: results from the chroma and spectri phase 3 trials. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(7):673-688.